D.C. LOSES A LEGEND

[December 18th] -- It's been quite some time since a Washington baseball team had a star shortstop. Not Felipe Lopez or Cristian Guzman. Not Eddie Brinkman or Ron Hansen or Ken Hamilin. Coot Veal didn't make it to the All-Star game. Neither did Jose Valdivialso, Billy Consolo or Rocky Bridges. Pete Runnels came close, but Sam Dente, Mark Christman, Gil Torres and John Sullivan didn't.

[December 18th] -- It's been quite some time since a Washington baseball team had a star shortstop. Not Felipe Lopez or Cristian Guzman. Not Eddie Brinkman or Ron Hansen or Ken Hamilin. Coot Veal didn't make it to the All-Star game. Neither did Jose Valdivialso, Billy Consolo or Rocky Bridges. Pete Runnels came close, but Sam Dente, Mark Christman, Gil Torres and John Sullivan didn't. In fact, you'd have to go all the way back to 1941 to find a superstar at short for the Washington Senators/Nationals.

Meet Cecil Travis. Sure, Travis played with Washington until 1947, but he wasn't a superstar anymore. He was barely a baseball player. Cecil Travis was done by the age of 34.

Travis died over the weekend at his home near Fayetteville, Georgia. He was 93. For most baseball fans, Cecil Travis was an unknown commodity, just another old guy in another obituary that listed "professional baseball player" as a past vocation.

But What Cecil Travis did, and didn't do, deserves so much more than a couple of column inches in his local paper.

With apologies to Joe Cronin and Roger Peckinpaugh, Cecil Travis was the best shortstop to play in Washington. And he was one hell of a man as well.

He arrived in Washington in 1933, replacing an injured Ossie Bluege, who was better defensively but didn't hit as well as the young Travis. He was given the opportunity to beat out Bluege that spring training, but the Washington Post reported that his effort to do so missed "by several comfortable miles." Travis' call-up was intended to be only temporary, but his 5-5 first game performance that helped the Senators beat the Indians 12-10 guaranteed his place on the Senators' Roster for the remainder of that year. Travis was a slap hitter adept at lining the ball the opposite way. As he gained experience, however, he learned to hit the ball to all fields, and became good at lining the ball down the lines, choosing to use the relative short distances at the foul poles in most parks of the time rather than the deep distances from left-center to right-center fields. Travis didn't have much power, but my-oh-my, the guy sure could get on base. He had a .374 on-base percentage during his first seven years with the Senators.

Travis was in the middle of a fight between manager Bucky Harris and owner Clark Griffith in 1935. In August, reports began to surface that Harris was considering moving Travis to the outfield, which angered Griffith. "If we could strengthen the team by moving him to the outfield, of course, we would do that, but that is not our present situation," Griffith told the Washington Post. "In the first place, who is there that we have who is a more valuable infielder than Travis? All the talk of making an outfielder out of him has been caused mostly by his heavy hitting. If his hitting were not so valuable, we wouldn't think of using Travis in the outfield, where we need hitting strength." It turned out that Harris wanted to bring up hard-hitting Buddy Lewis from Chattanooga to take Travis' place. In the end, however, Travis played just 18 games in the outfield before ultimately being moved from 3rd base (where he'd played since '33) to short, where he remained for the balance of his career.

Cecil Travis was a "gentlemen" on the field and didn't like to fight or retaliate when opposing players came into second with "spikes high." Griffith took this to mean that his infielder was "soft." Several times during his first season as a shortstop in the big leagues, Travis had been run over by opposing players. The Washington owner wrote Travis during the off-season that he expected Cecil to become more aggressive in his play in the middle of the diamond. Griffith wanted Travis to swing back hard if he felt the spike s of enemy runners. Travis had no problem with that request, under one condition: "If Mr. Griffith wants some punching done and will pay the fines, that's okay with me," Travis said, in January.

s of enemy runners. Travis had no problem with that request, under one condition: "If Mr. Griffith wants some punching done and will pay the fines, that's okay with me," Travis said, in January.

Travis, an average fielder during his career, committed 40 errors in 1938 and began the 1939 season just as poorly. An frustrated Clark Griffith offered Travis and any pitcher on the roster to the Detroit Tigers for their hard-hitting first baseman Rudy York, who had hit .298-33-134 the previous year for the Tigers. Hank Greenberg lobbied to keep his friend York, however, and the deal never materialized.

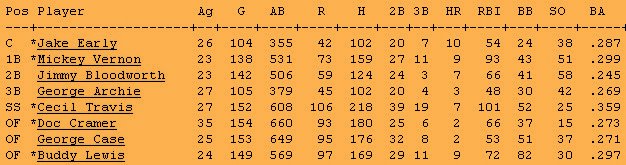

1941 was Travis' breakout year. In a season dominated by Boston's Ted Williams (.406 batting average) and New York's Joe DiMaggio (56 game hitting streak), Travis batted .359-7-101 with a .932 OPS. Travis' 24 game hitting streak was never covered in the media because it occurred in the middle of Joe DiMaggio's 56 game stretch -- still a major league record. His .359 batting average was second in the league (Ted Williams finished first, Joe DiMaggio finished third). Though Williams and DiMaggio were the hitting stars of 1941, it was Cecil Travis who lead the league in hits with 218. He was just 28 years old when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. In front of him was a 3,000 hit career and a .325 career batting average, both keys to the front door at Cooperstown.

Of course, that never happened.

Travis, like hundreds of other major league baseball players, lost four prime years from their careers. When he returned, he was a different player, batting only .236 in less than 700 at bats. It wasn't his ability. It wasn't his age.

It was the war.

Travis, like the rest of the American soldiers in the European theatre, believed the war was pretty-much over on December 16th, 1944, the day the Battle of the Bulge began. I ronically, Travis died exactly 62 years to the day after that battle began. Unlike many other major league baseball players -- especially the superstars -- who spent the war in supply depots playing baseball to "enhance the moral of the soldiers," Travis ended up being one of the "Battling Bastards of Bastogne," a group of out-manned and out-flanked American soldiers who held off superior German forces, ultimately allowing American reinforcements to push back the German offensive, ending all hopes of a German victory in World War II.

ronically, Travis died exactly 62 years to the day after that battle began. Unlike many other major league baseball players -- especially the superstars -- who spent the war in supply depots playing baseball to "enhance the moral of the soldiers," Travis ended up being one of the "Battling Bastards of Bastogne," a group of out-manned and out-flanked American soldiers who held off superior German forces, ultimately allowing American reinforcements to push back the German offensive, ending all hopes of a German victory in World War II.

Travis went days without food and water, surviving in the "relative" warmth and safety that his fox-hole provided. The cold took it's toll, however, as frostbite damaged both of his feet. Immediate surgery saved them, but damage to tissue and ligaments stole both his speed and balance. "We just followed in right behind the frontline troops," Travis recalled. "We were moving so fast taking all these towns that we just slept anywhere we could. And there were booby traps everywhere. But it was the cold that got to us. We just shivered all through the night long. I'll never forget that cold as long as I live."

Though his injuries brought him an automatic trip home and an end to the fighting, Travis nonetheless volunteered to be part of the group that was being formed to invade Japan. The "Enola Gay" and Col. Paul Tibbetts, however, ended the war before Travis could be shipped to the Pacific.

In 1941, he was considered the third best player in the American League behind Williams and DiMaggio. By 1946, he wasn't even the best shortstop on the Senators. The damage to his feet limited his defense, and his lack of balance at the plate made him an easy out. On August 15, 1947, the Senators held "Cecil Travis Night" at Griffith Stadium, presenting their veteran infielder several gifts. The ceremony included speeches by Washington owner Clark Griffith and Philadelphia owner/manager Connie Mack. At the conclusion of the season, Travis asked Griffith to place him on the volunt arily retired list. In January of 1948, he made it official, retiring quietly, just as he'd played most of his career, without much fanfare. "I saw I wasn't helping helping the ball club," Travis said, "so I just gave it up."

arily retired list. In January of 1948, he made it official, retiring quietly, just as he'd played most of his career, without much fanfare. "I saw I wasn't helping helping the ball club," Travis said, "so I just gave it up."

In the end, Travis was a three-time American League all-star. He was a hitting machine while healthy, which made it easier to overlook his defensive deficiencies. He had a strong and accurate throwing arm, and made an out of most every ball he got to. The problem was getting to the balls. His range was notoriously bad -- picture Jose Vidro last year.

Yeah, that bad.

Ted Williams was asked in 1997 just how close DiMaggio was to being the best hitter in the American League in 1941 (behind him of course). "Hell," began Williams, in 1941, Cecil Travis was just as good as either of us!" Asked to compare Travis' swing to a modern day player, Williams thought for a moment and replied, "He reminds me a lot of that kid Olerud. Sweet swing. Not a lot of power, but lots of doubles. Good sense of the strike zone."

How good was Travis? There are just two shortstops in baseball's Hall of Fame with a higher career batting average than Travis' .314.

That's how good.

But more than just a great player, he was a great man. He was one of Tom Brokaw's "The Greatest Generation," men who gave the prime of their lives to protect his fellow countryman.

What did he say about lo sing a sure Hall of Fame career by serving in the military? "Ah, I did the right thing. I'm proud of that. Baseball is just a game"

sing a sure Hall of Fame career by serving in the military? "Ah, I did the right thing. I'm proud of that. Baseball is just a game"

Perhaps in death, Cecil Travis' accomplishments will be better remembered then they were in life.

A great man. A great baseball player.

Who could ask for more?

I like the little sign for my link. I was wondering if you could show me how to put a logo in the page on the top. If you look at mine it has words. I have tried to replace that with a Logo I have made.

Thanks for the help and keep up the good work

He said he had "rock hands," but he could hit line drives all over the field.

Hope that helps

Farid

<< Home